Pittsburgh Center for Arts and Media: Executive Director Kyle Houser at the Helm

December 04, 2020

With a 75-year history as one of Pittsburgh’s major arts organizations, Pittsburgh Center for Arts and Media (PCA&M) has weathered many changes. Founded as a conglomeration of individual art groups in 1945 as The Arts and Crafts Center, it grew to become a nexus for art education and exhibition with a unified vision and strong leadership. When the center’s current Executive Director, Kyle Houser joined the organization in 2013, a decade of uncertainty had left the group in financial difficulty and organizational turmoil. Houser’s dedication to rebuilding the center’s strengths contributed to a major reorganization in late 2019. Houser says, “2020 was the year to turn the ship around. Unfortunately, in March, we hit an iceberg.”

Though the world-wide pandemic of 2020 has hit the center hard, the serious work of restructuring a large arts organization may have provided the groundwork for a resilient response to the devastation and its subsequent economic disruption. Houser says, “The restructuring was really all about making a hard financial decision long in the making. We looked at what was really working, and that was education. Teaching was and always had been the heart of our mission and we decided to double-down on that.” As the center adjusted to the restrictions of the pandemic, the educational mission provided the direction for a new plan.

The center has a visible presence in the community, especially with its wide selection of children’s summer day camps. So many of the artists who teach at the facility today had their first art experiences on the lawn in Kid’s Camp. Ceramics and visual art dominate the adult education offerings, with over 40 classes filling the center’s studios each term before the pandemic. When the center merged with Pittsburgh Filmmakers in 2006, media arts joined an ever-growing list of new disciplines. A studio membership-based group of artists and interested parties makes use of the onsite facilities when there are not classes in session. The center also administers the Artists in Schools and Community program, which serves over 12,000 public school students in four counties, with on-site artists-in-residence.

Houser first came to the center looking for studio space. “I wanted a studio,” he admits, “and was willing to take an hourly wage for a part-time position in the ceramics department in order to get that.” A native Floridian, Houser studied studio arts at Florida State University and took a job in elementary art education after he earned his degree. “I’ve always been a teacher,” he says. “I taught overseas, in high schools, and at the college level.” His wife is from Beaver County, Pennsylvania, which brought the family to the area in 2004. Houser enrolled with a full scholarship at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in the Ceramics program and earned his M.F.A. while working as an assistant to the department. Afterwards, he taught at IUP and worked for the School of Art within the Chautauqua Institution in Western New York during the summer session. When he took the part-time position at PCA&M, he found that his experience in non-profit organizations at Chautauqua helped him in reorganizing the ceramic program and the center’s educational programs in general. He became the Creative Director in 2018 and shortly thereafter was promoted to Executive Director. By the start of 2020, it looked as though things were looking up for both Houser and the PCA&M.

When the center closed and classes came to a sudden halt in March, Houser says they had just finished a wonderful winter term. “The world put the brakes on,” he laments, “and I didn’t know how we could continue. Everything we do is hands-on by nature.” The majority of the employees were furloughed, and Houser got to work seeking help. “Luckily, “he says, “we have a good relationship with financial institutions after the complex reorganization, so we were able to work with them for some assistance.” Within four weeks, Houser and his staff had crafted a plan to continue offering an educational program and workspace for artists. “We were first in line for the zoom workshop on the PPP (Paycheck Protection Plan),” he says, “and with the bank’s assistance, we were soon able to bring the staff back and start working in the ‘new normal.’”

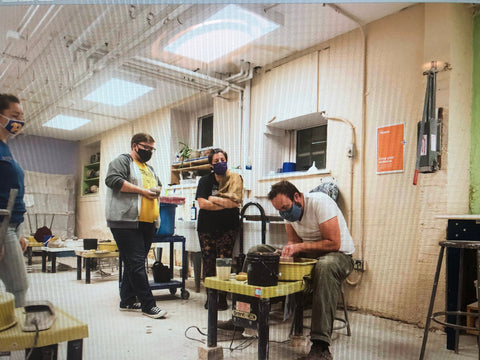

In June, the center reopened with a new arrangement for member artists who wanted to use the studios, emphasizing detailed plans on how to keep the work environment safe. Access to the ceramic studio, which is on the ground floor, was limited to one entrance. The first-floor painting studio was likewise limited. “We set things up,” Houser says,” so that the various groups would have no contact with each other coming and going from the facility. We made masks mandatory at all times inside the building, to accommodate newly restructured in-person classes as well.” Working with his Ceramics Department Coordinator, Audra Clayton, Houser oversaw an extremely organized schedule of appointments for specific areas of the studio. If a member needed to use the wheels or glaze a piece, he or she could schedule a private session in the throwing area or glazing area. “So many of our members have other jobs,” Houser says, “so they need a wide variety of access times.” The studios opened on the same time schedule as pre-pandemic – 6 days a week, including two evenings. Houser was pleased and relieved that the majority of the member artists continued with their affiliation.

Classes created a bigger challenge, but the center’s committed group of teaching artists were able to quickly adapt. Once again, the reorganization serendipitously offered some solutions. Houser says, “When we merged with the Filmmakers, we acquired a great deal of equipment that was perfect for taking things online, along with a few very tech savvy staff members who made the transition even easier. We went ZOOM ZOOM ZOOM right away.” During the summer, students could pick up a clay class kit, just like a carry-out meal, without any human contact. The short 4-week classes were taught online and students could drop off finished pieces for firing at the end of the course. By fall, Houser wanted to try a hybrid model with limited in-person classes, and a reduced student body capacity, but enrollment was disappointing. With the current surge in cases, the on-line classes are popular and are well-attended. Along with ceramics, PCA&M currently offers painting, drawing, printmaking, creative writing and a myriad of media arts classes and workshops online. A handful of classes that just could not translate well to the online format are offered in the center’s studios. [Visit www.pghartsmedia.org to see a full list of offerings.]

While the focus on education provided a direction for the pandemic plan, the complete educational offerings are by no means available. The children’s summer camp program is a major part of PCA&M’s financial well-being. Houser says that the loss of that income from 2020 and possibly 2021 is an enormous blow. Alternative virtual camps and limited in-person camps are planned for the summer of 2021, but whether parents will feel confident to send their children remains to be seen. Based on the success of the adult on-line model and because children have had months of on-line education experience now, that option could be successful.

In the midst of so much change and administrative work, Houser’s work as an artist has undergone some changes, too. He says, “I know many young artists are very comfortable with the online selling option, but I have been a bit overwhelmed by it, considering everything else that was happening – in the world and in my other role as director.” Houser has been part of a strong group of Indiana County potters who launch a popular tour and sale each year. He also participates in the popular Highland Park Pottery Tour here in Pittsburgh. Both events were canceled this year. For many years. Houser made sculptural vessels layered with imagery but found himself returning to his visual arts origins during the pandemic. “Graphics and images are part of what I do,” he explains, “and I’ve enjoyed returning to a more immediate art form, painting…of a sort! I’m focusing on the surface.” He considers himself an “art history-based person” and has been relooking at Japanese hand building techniques, such as kurinuki. “I always thought hand building was ‘ugh,’ but now I’m enjoying carving a vessel from a solid block of clay.” These new directions will have an outlet in a PCA&M exhibition and fund raiser, “Small Works and a Big Chimpanzee,” which opens on Saturday, December 5 and runs for two weeks. Admittance is by reservation to ensure safe social distancing. The work in the exhibition can be viewed and purchased at www.pghartsmedia.square.site.

The 2020 pandemic does indeed have the characteristic of a looming iceberg in the path of recovery and growth at PCA&M, but Kyle Houser’s leadership and skills have help to steady the ship. “Making art is an enormous part of my life,” he says, “and selling was a big part of my life. But teaching – passing it along – is so much more important.” For the students and artists at PCA&M, creating the opportunity to do that, in whatever form, is Houser’s most important work.